If last week was any early indication, 2016 will be a “bust” of a year. According to one analyst, “We’re just 11 days into 2016 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average is already down 6.2 percent for the year while the Russell 2000 small-cap index, which is on the verge of an outright bear market, is off 7.9 percent for the year and has lost 19.2 percent from its high set last summer.” Is there a guilty party for this sudden turmoil? Of course there is, and it is none other than China and a raft of questionable data points.

As Chinese officials desperately attempt to right the economic ship of the Middle Kingdom, the feedback loop of financial data from a variety of sectors is delivering a report card with poor marks, to say the least. One of the more troubling pieces of data has been the outflow of investment capital, as investors rush for the exits while the Shanghai Composite continues its freefall to who knows where: “From institutional data, we can observe that capital outflows from China are reaching record highs, with nearly $930 billion pouring out from Q2 2014 to Q3 2015.” Ouch!

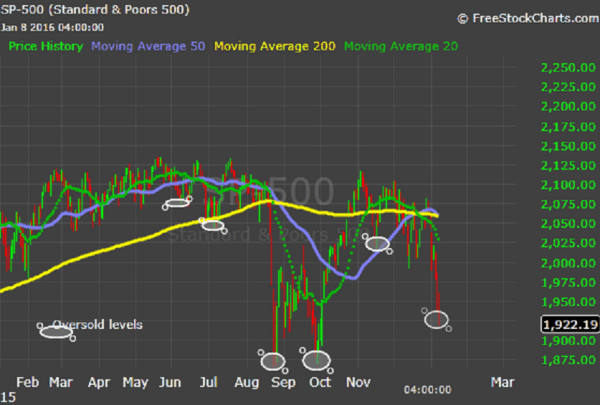

For the past month, technical pundits have been circulating their latest favorite chart that shows an eerie correlation between the S&P 500 and the Shanghai Composite indices. The only problem with it, which is substantial, is that the perspective shown is deceptive. Scale does mean something. For example, the two indices appear to move in tandem, but over the past six months, the S&P 500 fell only 8%, while the Shanghai exchange was off 24%. Yes, last week was a bad one, but, for the first two days of this week, the S&P has rebounded to the 1938 support level, thus countering an oversold condition:

Why the noise about China causing currency wars in Asia?

Much has already been written about the disastrous impacts on emerging markets that the slowdown in China has created. As economic activities lessened and infrastructure projects were completed or curtailed, the need to import raw materials, primarily from developing countries that depend on China’s support, waned. The precipitous and immediate drop in demand for the world’s hard and soft commodities from China has also led to a flight of capital from both China and its business partners, weakening national currencies right and left.

Currency depreciation has hit hard in places like Brazil, where a major drop has occurred. Political conditions in Brazil have not helped either, but the harsh pain related to cross-border purchasing power has especially been felt in Asian countries like Korea and Australia. Over the past four trading days of last week, the Korean Won fell roughly 3%, while the Aussie collapsed about 5%. The Japanese Yen actually strengthened, based on the news from China alone, but the Bank of Japan may have to intervene to keep its weakened posture reasonably intact.

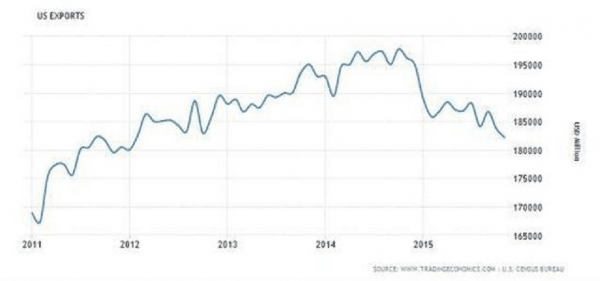

These changes are also not related to the Fed raising interest rates. Even Ben Bernanke, the former Fed chairman, has scoffed on his blog that to accuse the U.S. of orchestrating a currency war lacks sufficient evidence to give the argument any credence. To have a currency war, you must weaken your national currency, and the greenback has been in appreciation mode for some time. The primary objective for weakening exchange rates is to produce a boost in exports, but the stronger Dollar has produced the opposite effect, as any economist would expect and as depicted below:

So why have accusers jumped on a bandwagon to pillory China for igniting currency wars in the Pacific region? Yes, Chinese officials at the Peoples Bank of China (PBOC) carefully engineered a weaker Yuan last August, but the decline has been minimal by any measure. When the IMF voted to include the Yuan in their basket of Special Drawing Rights (SDR), then the furor subsided. Central banks could then use their Yuan positions for trade credit purposes without having to convert balances on the spot.

The Chinese Yuan remains a controlled currency. It is not freely floating, since the Chinese government forbids trading in derivatives, a must for hedging, and any active trading in the Yuan offshore. Small exchanges do dabble in an offshore value that tends to deviate slightly from the official version, but the PBOC has learned to intervene where necessary to maintain its quasi-peg to the USD. As for last week, the Yuan barely budged lower by less than 1%, hardly a call to arms from war enthusiasts. The argument that China is an instigator of a foreign exchange war just does not hold water.

Read more forex market news

If China is not a culprit, then what are foreign-exchange markets telling us?

The repeating cycle of capital flows leaving emerging markets for safe havens is not new news. The process this time around, however, has taken on a new and improved look, hyped up on steroids from Zero-Interest Rate policies (ZIRP). Technology and a more entwined global economy enabled investment portfolios to broaden their horizons like never before. Prior to 2000, the typical standard for offshore investments was 5%. This figure soon morphed into 10% and then 15%. When central banks introduced ZIRP, the race was on to find higher returns, which were more likely possible in some far off land.

In response to this demand, emerging markets have piled on the debt by issuing billions in bonds with higher paying interest rates. Bank trading departments have jumped with both feet into this global bond-trading casino, creating a near replica of the conditions that ignited the Great Recession meltdown. If there is a positive slant to the current malaise, it is that global money managers are better prepared to react this time around. Instead of waiting for the greatly feared liquidity crunch to appear when everyone heads for the exits at once, an enlightened few have chosen to adjust their portfolio allocations over the past few years. Massive carry trades have been unwound without the fanfare of blood in the streets.

The press has focused on the problems in Brazil and South Africa. Since the middle of 2011, the USD has trounced the currencies for both countries by a whopping 130%. The recent storyline has now shifted to Asia. As one analyst wrote, “The Asian countries seem to be moving together. Over the past six months, the Singapore Dollar and the Korean Won are down by 5 percent. The Taiwan Dollar has dropped by 7 percent. Even the Indian Rupee has fallen by about 7 percent against the Dollar.” While people fear that a downward move in China’s Yuan might exacerbate the situation, the real “devil” in this new-age drama appears to be our highly evolved open capital market system.

Today’s tealeaves are the pictures portrayed by the various flows in our forex markets. This analyst continues, “Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers writes in the Financial Times about why policymakers should pay attention to these flows and pay attention to what exchange rates are saying about what is happening in world financial markets. It seems as if the foreign exchange markets are saying that many countries within the world are having trouble growing and given their current debt loads, even more difficulties might be experienced in the world in the future.”

Is there really a possibility of a meltdown in China?

The word “contagion” has conjured up all kinds of miserable outcomes that could eventuate in Europe, due to its ongoing crisis with tepid economic growth and mountains of sovereign debt. The one region of the world that managed to sidestep the misery of the Great Recession, the Asia-Pacific region, is now finally coming to grips with slow growth and deflationary pressures. Doomsayers are already suggesting that contagion could spread from China, infecting their neighbors and trading partners first, and then causing havoc in the rest of the developed world.

If you buy into this line of logic, then it sounds like the “China Syndrome” in reverse. An economic meltdown in China under this scenario would pass directly through the Earth until it came out on the other side and destroyed the financial systems in both North America and Europe in its wake. Prepare yourself for an avalanche of articles on this theme. The press loves a good disaster story, but many authors will counter that China is an isolated experiment. It is de-coupled from the rest of the world. Not!

In the past four decades, China has become an integral component of the global economic community. It may still have currency controls, but the flood of capital leaving the country is already creating real estate “bubbles” in several pricy markets across the globe. Chinese officials have even encouraged local real estate holders to borrow on pumped-up values to invest in Chinese equities, another house of cards that is wobbling in the wind.

The key issue, however, is what we learned in early Economics classes about marginal supply and demand impacts. A large portion of a company’s revenue goes to covering both fixed and variable costs, but the marginal revenues provide a much higher level of profit, once the basic cost drivers are covered. Companies thrive on these marginal aspects, driven by scale benefits earned down the line. For the global economy, China represents these marginal supply and demand dynamics. In other words, small changes in China could ripple like some exaggerated “Butterfly Effect” across the planet.

Concluding Remarks

2016 has definitely gotten off to a rocky start. The flames of fear are already being fanned, and politicians have yet to begin their amplified rhetoric that will surely come during this presidential election year. Central bankers have been warning us for years that a liquidity crunch of enormous proportions was looming on the horizon and that chaos in the foreign exchange markets would be the harbinger of things to come. A few analysts have already focused on what currency markets are telling us on an overall basis, but will whatever transpires in China be the final catalyst for inescapable doom?

Stock markets have withstood last week’s onslaught. The 6% fall did not turn into a 10% correction. Crude oil has bounced off $30 a barrel, a new 12-year low. Gold and the Euro versus the USD have steadied. For the time being, the dreaded “China Syndrome” scenario is on hold, as the investment community breathes a collective sigh. Chaos will manifest itself at some time in the future, and you can be sure of one thing – The foreign exchange market will be the first to telegraph the volatility. Stay cautious!

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk  Your capital is at risk

Your capital is at risk