Crude oil is the world’s most heavily traded commodity. As a raw material to make goods and then as a fuel to transport them, crude literally oils the wheels of the global economy. It has also turned some major oil exporters into global economic superpowers.

Price moves in the oil markets can impact the value of the currencies of countries that are major producers or importers – the amount of revenue they receive on oil sales or expenditure on an essential item goes up or down. Trends in the oil price can also impact the broader global economy by triggering moves in inflation levels which have a knock-on effect on interest rates. And, despite the introduction of carbon-free energy sources, the oil-forex relationship looks set to continue to be a significant driver of prices in the currency markets.

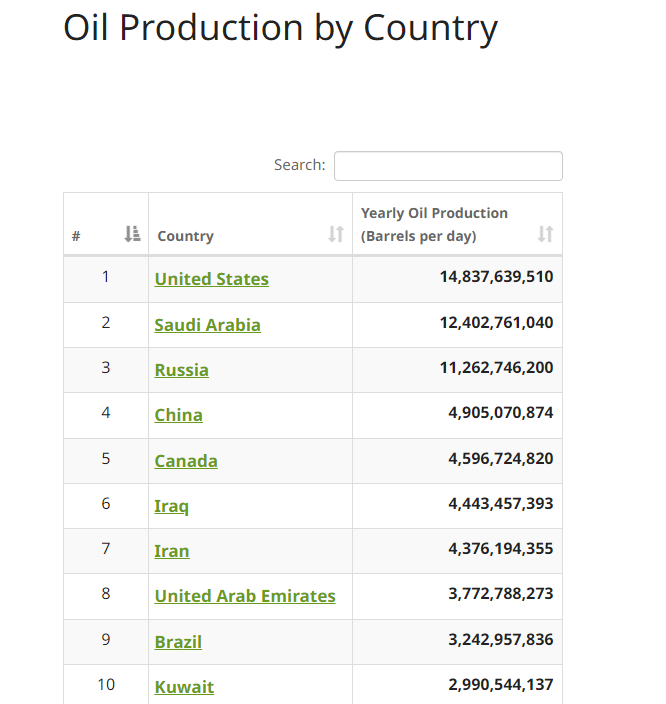

Which countries produce oil?

Oil’s critical role in the global economy means that any country with natural resources of the commodity has prioritised trying to exploit them. That helps them become less exposed to price moves in the global commodity markets and represents a step towards energy security should the global geopolitical environment deteriorate.

Even Germany, which is particularly exposed to oil price moves, has developed structures to extract what it can from its own territories. Germany currently produces 23% of the oil it consumes and ranks 35th in the global table of oil-producing countries.

Source: Worldometers

North America

The US and Canada rank first and fifth in the table of oil production by country. North America’s relatively stable geopolitical status offers some comfort to oil-importing countries. Global prices are, to some extent, stabilised by the reliability of the oil supplies from the region to countries that, due to political events and intervention, could otherwise be exposed to a supply reduction.

Canada produces more oil than it can consume. As a result, it is a significant net exporter of crude oil. The US has recently shifted from being a net oil importer to a net exporter, with the 2023 Annual Energy Outlook (AEO2023) from the US Energy Information Administration predicting the country will remain a net exporter until 2050.

Related Articles

The oil trading between the US and Canada highlights the importance of understanding how crude is categorised into different grades. Not all oil is the same, with some crude being better suited to being refracted to make high-end chemicals and some only good enough for an ingredient of asphalt to build roads. The exact details vary over time, but Canada was at one point exporting 97% of its production to the US while at the same time importing 54% of the oil it needs from the US.

Middle East

Geographically, the Middle East is a region of 17 countries located in Western Asia, extending into Egypt. The area includes five of the top 10 oil producers in the world and has a track record of playing a significant role in determining global oil prices. Efforts to diversify their income stream away from crude exporting include hosting the FIFA World Cup and developing tourist hubs. However, the price of crude on world markets still plays a role in determining the currencies of Middle Eastern countries.

Russia

Russia’s position as the world’s third-largest oil producer even survived the imposition of international sanctions following the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. With two major exporting pipelines affected, it simply transferred exports from the EU-bound Druzhba pipeline to the ESPO pipeline, which carries oil to China. Russia is expanding into new markets, most notably India, but it still exports much of its oil to China (20%) and the EU (44%).

OPEC and OPEC Plus

Oil is produced in 127 of the world’s countries, and some, such as Venezuela, Mexico, Norway, and Nigeria, make the top 20 in the chart of oil-producing countries. These countries may appear relatively isolated geographically, but they have currencies which are heavily influenced by the price of crude.

Some countries have joined the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries- OPEC to stabilise the price of oil and extract as many personal benefits as possible. That organisation was founded in 1960, with the original members being the Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela. Currently, the organisation has 13 members due to the addition of Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962), Libya (1962), the United Arab Emirates (1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973), Gabon (1975), Angola (2007), Equatorial Guinea (2017) and Congo (2018).

OPEC Plus is an extension of the core OPEC membership with additional oil-exporting countries such as Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Brunei, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Mexico, Oman, Russia, South Sudan, and Sudan.

How are oil and forex connected?

The economies of big oil producers have distinctive characteristics, and the value of their currencies is heavily linked to oil prices. That has resulted in a nickname sometimes being applied to countries heavily reliant on oil export revenues, that of ‘petrol-currencies’. When the price of crude goes up, every country wanting to buy oil from them needs to buy a larger amount of that country’s currency for each barrel purchased. When crude prices fall, so does demand for that exporting country’s currency.

As a result, the price of petrol-currencies can be seen to track the price of crude. Other factors can influence the strength of the correlation. For example, the US is the world’s greatest producer of oil but has high domestic demand, so net exports of oil are relatively low. It also has thriving other sectors ranging from banking to aerospace, and they play a large part in determining whether investors see it as an attractive proposition. Therefore, a decision to buy US dollars is relatively less closely linked to the price of crude than it is to Russian roubles or Canadian dollars.

There is also the ‘curse’ of oil to consider. Over-reliance on oil exports has historically left big oil producers struggling to grow other areas of their economy. The IMF predicts GDP growth in the Middle East will be 2.7% in 2023, a fraction of what is needed to create enough job opportunities for the fast-growing young, working-age population. Even in those few countries enjoying higher growth, poverty has failed to decline, indicating a need for further reforms to introduce fair competition and promote domestic growth. Struggling economies are associated with weaker currencies, particularly if government officials and industrial tycoons who profit from oil exports invest in overseas assets.

Oil and inflation

Oil is a common ingredient in many industrial products and consumer goods, including plastic bags and bottles, tyres, and numerous other items. Transport infrastructure systems are also heavily reliant on oil. So, oil price increases have a knock-on effect on manufacturers and the leisure sector, especially airlines. The service sector can also get caught up in oil price rises due to the need for workers to travel to work or on business trips.

As such, it’s safe to say that the price of oil has a direct relationship with inflation. Especially producer price inflation at the factory level, which determines trends in the price pipeline. Also, due to the heavy weighting of fuel in the consumer’s basket, oil prices have a far greater transmission rate from the wholesale to the retail level. They are also more relevant to the CPI than other commodities.

All of these factors make central banks attentive to trends in this market. It is not unusual to see a particularly hawkish central bank acting pre-emptively to forestall anticipated inflation by raising interest rates in response to oil price trends before such trends are felt in the consumer’s pocket. Given how important interest rates are to forex trends, the importance of the oil market is not difficult to observe.

It’s also worth circling back around and considering how economic growth, inflation, and interest rates can, in turn, influence the price of oil. During recessions or times of geopolitical uncertainty, demand for oil can slump. The slump in travel miles seen during Covid lockdowns, for example, slashed the demand for oil. As oil prices hit record-low levels, many operators were forced out of business. Given how long it takes for supply to come back on tap, that caused a rebound in oil prices when lockdowns were lifted, and supply struggled to keep up with demand.

People Also Read

Summary

There is no denying that oil is one of the most important commodities worldwide. It has played a vital role in forming economic trends and will undoubtedly continue to influence a wide range of financial markets in the coming decades. Traders of currencies such as the Canadian dollar and Russian rouble do well to keep one eye on the oil markets. Price moves there can often explain changes in forex rates. And if you can spot a trend in the oil price, you might be able to apply that to a trading strategy relating to a petrol currency.

Choose one of our Top Forex Brokers

| Broker | Features | Regulator | Platforms | Next Step | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2014 Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2014 |

|

FSPR | MT4 | ||

Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2006 Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2006Europe* CFDs ar... |

|

ASIC, FSA, FSB, MiFID | MetaTrader4, Sirix, AvaOptions, AvaTrader, Mirror Trader | ||

Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose

Founded: 2010 Between 74-89% of CFD traders lose

Founded: 2010Between 74-89 % of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs |

|

ASIC, FCA | MetaTrader 4, MetaTrader 5, cTrader | ||

Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2009, 2015, 2017 Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2009, 2015, 2017 |

|

ASIC, CySEC, IFSC | MT4 Terminal, MT4 for Mac, Web Trader, iPhone/iPad Trader, Droid Trader, Mobile Trader, MT5 | ||

Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2006 Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2006 |

|

CySEC, DFSA, FCA, FSB, SIA | MetaTrader4, MetaTrader5, cTrader, FxPro Edge (Beta) | ||

Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2011 Your capital is at risk

Founded: 2011 |

|

CySEC, FSC, FSCA, MISA | MT4, MT5, OctaTrader | ||

Forextraders' Broker of the Month

BlackBull Markets is a reliable and well-respected trading platform that provides its customers with high-quality access to a wide range of asset groups. The broker is headquartered in New Zealand which explains why it has flown under the radar for a few years but it is a great broker that is now building a global following. The BlackBull Markets site is intuitive and easy to use, making it an ideal choice for beginners.